|

‘Mikró Horió Bar’ is the only ‘real’ discothèque in Tilos, opening every night (during the summer) at midnight. The dance floor and the dj’s equipment are located on a terrace with a great view over the hills, Livadia’s bay and the sea, and the starry sky. Due to the small tourist development both of Tilos and of the Knidos peninsula in front, this is one of the least light-polluted areas in the Mediterranean. The two powerful JBL acoustic systems fill the valley with sounds: often the dj starts with Greek music (singer-songwriters from the éndechno genre), or old rock classics, and then move to contemporary pop an dance, both Greek and international. Not too many foreign tourists, however, enjoy listening to Pink Floyd’s The Great Gig in the Sky under a wonderfully detailed Milky Way, as a tourist’s life in Tilos is quite tiring, and after a day of walks and swims many do not make it to midnight. So Mikró Horió’s disco is mostly visited by Greeks, either young people who work during the day in Livadia, or expatriates back home on holiday from Australia, New Zealand, Canada or the USA, who consider other Europeans who spend their holidays in Tilos walking one or two hours to get to a solitary beach, under a fierce sun (and more hours to get back), rather mentally disturbed. Two other bars, Bozi in Livadia and Ilakathi in Megalo Horió, feature the same attendance. So, in Tilos there isn’t actually a discothèque that can be compared to the ones foreign tourists usually look for and find in most other Greek islands, and lovers of that kind of nightlife very quickly become disaffected to the island, and after a short stay move elsewhere. The lack of an airport also discourages packaged tourism: there aren’t big hotels on the island, and people wanting

The beach in the bay of Livadia is about three km long, with tamarisks growing in the back. During a normal summer day, you will see a few tourists (about three or four) in the shade of each of the tamarisks, regularly spaced. But there is just one spot, about fifty meters long, where the population density becomes much higher, ghetto blasters play dance music, and muscled animateurs entertain a crowd that seems to have passed exams for a Berlusconi TV reality show. That’s Tilos Mare. Sometimes they are taken by boat to some of the remote beaches, where they find other tourists (Greek, Italian, British, French, German, Dutch, and recently also from Spain and Israel) who arrived there by foot, and they are surprised and a bit disappointed.

Every summer in Tilos there is a number of religious festivals: on July 25th to 27th at the monastery of Agios Pandeleímonas, an ancient but perfectly functioning monastery from the Middle Ages (there are no monks living there: just rooms for occasional pilgrims), located high on a cliff in the most Northern part of the island; on July 28th in Megalo Chorió, in the small square near the church; on August 14th in the little church in Mikró Chorió; on August 22nd in the sanctuary of the Holy Virgin (Panaghía Polítissa) on the hills SE of Livadia, and - in apparent competition - in the small monastery of Kamarianí, near the village of Agios Andonis; on August 23rd again in Megalo Horió.

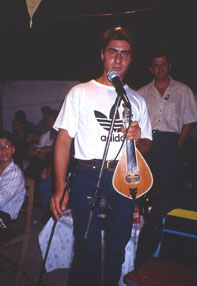

Music has obviously a great social significance in these events. First, it is a matter of pride for the organising committees that the best musicians be invited (with perceivable competition amongst the festivals and related communities): most of the times, musicians come from islands in the Southern Dodecanese or Crete.

I have recordings from a group from Kassos and a few groups from Crete: one of them (for Agios Pandeleimonas festival in 1997) arrived by ferry escorted by an ‘official’ Mercedes with banners, with a hero of Cretan resistance (in traditional costume) who led the dances along with the island’s mayor, adding the sound of his Beretta pistol to the lyra, laouto and doubeleki of the greatly competent music trio.

proper hierarchy is respected. Kids learn to be last in the line, and sometimes bands dedicate ‘easy’ dances to the children.

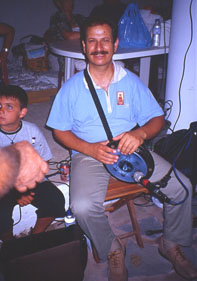

But I saw interesting variants, like a keyboard-based one-man-band, or a ‘traditional’ trio (From Halki) accompanied by a rhythm box (very well programmed).

|