Author: Adam Laye, Randallstown High School, Baltimore County Public Schools

Grade Level: High

Duration: 1-2 40-minute periods

Overview:

Who bears the responsibility for the deaths of 146 young female workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City on March 25, 1911? This debated question serves as the springboard for an investigation of this infamous workplace fire. Widely known as one of the worst industrial fires of the Progressive Era, an analysis of the causes and outcomes of the Triangle factory fire will show students how disasters can be the impetus for reform of workplace conditions. The topic also provides insight into gender relations, urbanization, and the daily lives of new immigrants in early twentieth-century America.

As students sift through the documents in this History Lab, it becomes obvious there is no simple or definitive answer to the focus question. Initially students may want to assign all responsibility to the factory owners, but they will find the waters get murky as multiple eyewitness accounts and ineffective building codes attest. Further, statistics revealed that the government at the time was hard-pressed to enforce even minimal safety regulations, and that thousands of other factories throughout New York faced the same dangers. It is through the navigation of this convoluted historical evidence that students will realize that assigning responsibility for any disaster is rife with complexity and contradictions.

National History Standards

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Standard 2: Massive immigration after 1870 and how new social patterns, conflicts, and ideas of national unity developed amid growing cultural diversity.

Standard 3: The rise of the American labor movement and how political issues reflected social and economic changes.

Historical Thinking Standards

Historical Comprehension

A. Identify the author or source of the historical document or narrative and assess its credibility.

D. Differentiate between historical facts and historical interpretations.

E. Read historical narratives imaginatively.

Historical Analysis and Interpretation

B. Consider multiple perspectives.

C. Analyze cause-and-effect relationships and multiple causation, including the importance of the individual, the influence of ideas.

Historical Issues-Analysis and Decision-Making

A. Identify issues and problems in the past.

D. Evaluate alternative courses of action.

E. Formulate a position or course of action on an issue.

Maryland State Curriculum Standards for United States History

History Objective-Examine the economic, political and social impact of industrialization.

Purpose:

In this History Lab, students will analyze documents related to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire to determine who was responsible for the fatalities that resulted. In doing so, students will:

- Examine industrial working conditions at the turn of the century

- Explore early 20th century gender relations, since most of those who died in the fire were young women.

- Consider the efforts of urbanization on the daily lives of "new immigrants" to the Northeast.

- Examine how disasters often provide an impetus for reform.

In utilizing newspaper accounts of the fire, as well as the trial that followed, students should be able to determine who shares what portion of the responsibility for the deaths of the 146 employees. Ultimately, students will understand that no single individual was culpable - it was multiple parties and myriad failures that led to one of the worst industrial disasters in American history.

Lab Objectives:

- Identify the facts surrounding the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

- Analyze public responses to the tragedy

- Determine the significance of the fire

- Assess the impact of authorship on the investigation

- Assess the degree of responsibility for multiple parties in the deaths of the employees

As we remember the one-hundred year anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, it still remains one of the most deadly workplace disasters in American history. In just under 30 minutes, a raging fire on the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors stole the lives of 164 young women. Unsurprisingly, the reaction from Americans was one of shock, horror, and outrage; someone was surely to blame. Was it the building owners who violated the most basic of building codes? Was it the factory owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck who chained the fire escape doors? Was it the fire department whose response time was less than desirable and ladders proved insufficient to reach the women engulfed in flames? Could it be the careless workers who smoked cigarettes on the job while the floor was littered with scraps of textiles? Or, was it the government who provided a futile oversight, if at all, over the lords of machinery? Even 100 years later, the blame game is still played but more importantly, the question still remains. What could have been done differently to avoid this travesty?

New York City was the most densely populated urban area on the planet at the turn of the century. "New Immigrants" from southern and eastern Europe flooded through the gates of New York looking for opportunity and seeking a new life. While some of them indeed pulled themselves up by their bootstraps and made their fortunes, the vast majority remained easy prey for the industrial giants. The seemingly endless tide of labor allowed management to manipulate workers, keep wages low, and pit ethnic groups against each other. The most vulnerable of the laboring population were surely the women, especially those who did not speak the native language. While a few charismatic immigrant women tried to organize female laborers, their unions remained relatively weak and unable to make much progress with management. As a result, most women in sweatshops worked in squalid conditions for minimal wages.

The conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City were not unlike thousands of other sweatshops in the Industrial era. This was not a sprawling mill complex of power looms weaving endless miles of cloth. Rather, it was a sweatshop which occupied two floors of the Asch building in the current Greenwich Village which totalled 10,000 square feet.1 The factory operators were mostly young immigrant women ranging in age from their teens to upper twenties. They were Jews, Italians, Poles, and other Southeastern Europeans performing hard labor for menial wages. The factory owners were Isaac Harris and Max Blanck who made handsome profits by subcontracting labor to individuals. The young women often worked six days a week with hours that ranged from 50-70 hours, often with no overtime pay. Employees could be penalized pay for a myriad of reasons: talking on the job, missing a shift on Sunday, or taking too long during a restroom break, among others. Sweatshop employees sometimes had to pay to rent for their seat in factories, to replace their sewing needles if they broke, and even pay the electricity costs of operating the machine. They worked long hours in cramped quarters and strained their eyes due to inadequate lighting. Sometimes they would shift their sewing machines closer to the windows during daylight hours in order to see. The long hours were most certainly strenuous on the hands, the back, the eyes, the mind. The result was a socially stifling atmosphere and one of fear and frustration.2

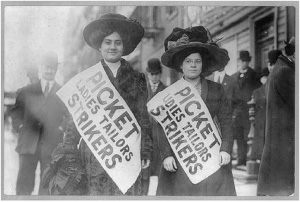

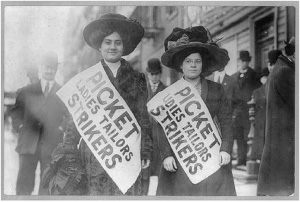

Sweatshop employees did not willingly accept those conditions nor did they make no attempt to address them. Most notable among their efforts to secure safer working conditions and better wages preceding the Triangle Factory fire was the Uprising of 20,000. In the fall of 1909, female garment employees across New York City were being pressured, once again, to produce more goods for lower wages. The International Ladies' Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) immediately called a meeting to discuss general strike. Thousands of garment workers from all over the city attended the meeting in which they discussed the prospects of a general strike on November 22, 1909. American Federation of Labor President Samuel Gompers spoke and encouraged the women. The young and charismatic 19 year old Clara Lemlich took the podium and told her fellow garment workers in Yiddish, "I have no further patience for talk as I am one of those who feels and suffers from the things pictured. I move that we go on a general strike...now!" The following morning, fifteen thousand garment workers across the garment district of New York walked out. As picketing ensued, a total of twenty thousand shirtwaist makers from across the city entered into a general strike. The women demanded an established 52 hour work week for all shirtwaist makers, a wage increase of twenty percent, a guarantee of overtime pay if they exceed 52 hours in a week, and a closed shop. Though some of the smaller factories immediately made the concessions, t he majority of the largest employers did not. Exerting their power with capital, thugs were hired to attack and intimidate the strikers. In tandem, factory owners used their political connections with local police forces to obstruct the strikes and arrest the strikers. Women were fined and sometimes sentenced to forced labor by local judges. The public response to overt brutality and corruption was widespread. An additional fifteen thousand shirtwaist workers walked off the job in Philadelphia. A month later, public opinion forced the larger employers to negotiate with the ILGWU and by February of 1910 the strike was over. Management agreed to some concessions including wage increases and better working conditions and the strikers returned to work without a union agreement. Without a contract, the result was minimal gains as most employers refused to honor their agreements, therefore upholding the status quo.3 Though the women viewed the strike as a victory, its failure to secure lasting change led to future industrial disasters.

Perhaps the first sign of the ineffectiveness of the strike was in Newark, New Jersey. Eight months after the strike ended, a fire erupted at the corners of Orange and High Streets on November 26, 1910. On the fourth floor of the building, a fire broke out in a lamp factory. When the fire spread, the foreman was able to unlock the doors to the exit, luckily, and allow most of the employees a safe escape down the stairs. However, nine girls were burned to death in the fire and sixteen jumped to their deaths from the windows. There was no fire alarm and the fire escape outside the windows failed. Public outrage demanded that laws be enacted to curtail future disasters and ensure employee protection; nothing happened.4 The parallels are noteworthy to the coming Triangle disaster.

On March 25, 1911 the young women returned to work on the eighth, nine, and tenth floors of the Asch building. It was a routine day at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory until approximately 4:40pm, 15 minutes before quitting time, when a fire erupted on the 8th floor. While only speculative, it is widely believed that the fire started in a trash can from an employees cigarette or unlit match. Once the fire started it force could not be contained; the textile scraps littering the floor became kindling for a ferocious fire that spread quickly to both the ninth and tenth floors of the building. Most of the girls on the eighth floor were able to escape to the stairs and the elevators but within minutes the elevators were engulfed in flames and rendered useless.5

On the more crowded ninth floor, the most dramatic events unfolded. Stunned by the suddenness of fire, some girls failed to react at all and died still seated at their sewing machine. There were only three possible options for escape: the elevator, the exit door, and the fire escape outside the window. The elevator was already inoperative and some of the employees jumped to their deaths down the elevator shaft. Other girls panicked and bolted towards the escape door only to find that it was impossible to open. Some employees alleged that factory owners Harris and Blanck had locked the doors that weekend to prevent the theft of shirtwaists, an allegation that was never proven. Regardless, in the mad rush to the exit door the girls may have trapped themselves because the doors opened inwards which would have been impossible when scores of women were pushing forward. The last option, the fire escape, was almost instantly rendered useless when the flimsy metal frame was melted.6 The failure of these three avenues of escape resulted in an industrial calamity of epic proportions.

With no other option women tried the windows as a last resort, many jumping from the windows in a panic with their clothes and hair ablaze. Some stood at the ledge of the window crying and holding one another before jumping together and free-falling 90 feet. A crowd quickly gathered at Washington Square and witnessed the women hitting the sidewalks by the dozens. No one could do anything but stand in complete horror as the safety nets failed and the fire departments ladders were far too short to reach the ninth floor.7 By approximately 5:05pm the fire had claimed 146 victims.8 The worst industrial disaster to ever occur in New York City was over.

The public response was one of outrage, shock, confusion, and sadness. Media publications across the country ran articles about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. People tried to understand how something like this could happen and what could be done to prevent it from happening again. The fact that the victims were predominantly young women between the ages of 16-23 created a greater sense of urgency to achieve justice and devise preventative measures. When journalists caught wind that the factory owners Harris and Blanck may have locked the doors of the 9th floor there was a tangible public backlash against them, even in the less sensational publications. In mid-April, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck were indicted for manslaughter on two accounts. It was the burden of the prosecution to prove that Harris and Blanck had willfully and deliberately locked the factory doors on the day of the fire. The highly publicized trial was filled with emotionally charged testimony and contradictory accounts of what occurred during the fire. Some of the girls testified that Harris and Blanck had indeed chained the door shut that day.9 Contrarily, other witnesses testified that the doors were not locked that day and if the doors were ever locked that there was always a key in it.10 Three days after Christmas of 1911, the jury voted to acquit Harris and Blanck of their charges. The justice system had denied the public a singular scapegoat for the tragedy.

Public sentiment also strongly condemned the government. It had not been a secret that the sweatshops of New York were likely to face a major disaster like the Newark fire in 1910. In a cruel irony, a public report 9 days before the fire stated that most sweatshops lacked "even the most indispensable precautions necessary." In fact, the Triangle Shirtwaist factory had passed a routine fire inspection one month before the Newark fire.11 The prevailing view was that the government had failed to create effective safety regulations and had absolutely no teeth to enforce compliance with the minimal safety standards that did exist. Two days after the fire, the chairman of the Fire Prevention Committee testified there were hundreds of thousands of safety violations across New York City and called the current regulations "far inadequate and, indeed, a delusion and a sham."12 It became clear the government had a responsibility to amend its building codes, improve fire inspections, adopt new fire escape regulations and effectively enforce these policies.

The Triangle Shirtwaist fire provided impetus for reform, but it did not come without a struggle. New York Fire Chief Edward F. Croker issued a scathing criticism of the local government for failing to fund the FDNYC and follow his fire-fighting recommendations long before the Triangle fire. As a result, he quit shortly after the fire. Despite Croker's cynicism and frustration with bureaucracy, many new regulations were adopted by the government. A Fire Inspection Commission was formed to design legislative recommendations to the municipal government; many of their recommendations became law. All factory doors were required to open outward. Elevator shafts had to be closed to prevent people from jumping down the shaft. Limits were placed on the amounts of employees per floor and additional fire exits had to be constructed. Fire alarms in any building above two stories high became mandatory. In 1912, New York City required sprinklers on every floor above the seventh floor. In order to enforce these new policies, the labor department was expanded, more building inspectors were appointed and fire-fighting science was improved.13

In the end, no one truly bore sole responsibility for the deaths of 146 employees at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck were acquitted for manslaughter and were later brought back to court for civil suits. They eventually settled and paid $75 per death. However, the insurance company paid Max Blanck $400 per victim, making him a profit of $60,000. Blanck would go on to own other sweatshops and, in an unrelated event, would later be fined twenty dollars for chaining the exit locked at a different factory in 1913.14 Since the building owners did not break any laws, they were not forced to pay any fines. At the governmental level, no one lost their job. This is, however, indicative of the nature of such a disaster. Culpability did not rest with a single individual or institution, it was a collective failure. Most importantly, it was a catalyst for change and steps were taken to prevent another such tragedy. The new regulations provided a solid model for other municipal and state governments to follow. New York would not experience another workplace disaster of this magnitude until two airplanes flew into the Twin Tower buildings on September 11th, 2001.

1 "Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial: Building laws." Famous Trials. http://law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglescodes.html (accessed August 5, 2010).

2 "Sweatshops and Strikes before 1911." The Triangle Factory Fire. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/Trianglefire/photos/photo_display.html (accessed July 19, 2010).

3 "Uprising of 20,000 and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." ALF-CIO. http://www.aflcio.org/aboutus/history/history/uprising_fire.cfm (accessed August 5, 2010).

4 Hopkins, Mary Alden. McClures, April 1911. http://www.oldnewark.com/histories/factoryfire01.html (accessed August 5, 2010).

5 Davis, Hadley. "Reform and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." The Concord Review (1988). 1-12. http://www.tcr.org/tcr/essays/Web_Triangle.pdf (accessed August 5, 2010).

6 Davis, Hadley. "Reform and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." The Concord Review (1988). 1-12. http://www.tcr.org/tcr/essays/Web_Triangle.pdf (accessed August 5, 2010).

7 Davis, Hadley. "Reform and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." The Concord Review (1988). 1-12. http://www.tcr.org/tcr/essays/Web_Triangle.pdf (accessed August 5, 2010).

8 The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial: A Chronology." Famous Trials. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglechrono.html (accessed August 3, 2010).

9 "Excerpts from Trial Testimony in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial." Famous Trials: The Triangle Shirtwaist Trial 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/triangletest1.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

10 The New York Times. "Say Triangle Doors Were Never Locked: More Witnesses Contradict the Testimony of Harris & Blanck's Girl Employees" December 21, 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglenyt1221.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

11 The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial: A Chronology." Famous Trials. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglechrono.html (accessed August 3, 2010).

12 McClellan, Jim R. Changing Interpretations of America's Past. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. McGraw Hill, 2000.

13 Davis, Hadley. "Reform and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." The Concord Review (1988). 1-12. http://www.tcr.org/tcr/essays/Web_Triangle.pdf (accessed August 5, 2010).

14 "The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_Shirtwaist_Factory_fire (accessed August 7, 2010).

Shirtwaist - a highly fashionable and popular women's blouse (shirt) from the early 20th century. It was regarded as the "model shirt for the independent, working woman."

Yellow Journalism - sensationalized reporting which predated tabloid journalism.

International Ladies' Garmet Workers Union - Labor union which represented the interests of female factory workers.

Uprising of 20,000 - organized strike of female shirtwaist makers in New York in 1909.

Labor Regulations - governmental laws which guide workplace safety and guidelines.

Francis Perkins - labor activist who, as Secretary of Labor, was the first female cabinet member under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Proprietor - owner of a business.

Culpable -deserving of blame

Overarching Question:

Who should bear responsibility for the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire?

To answer this question, students will complete an investigation of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire to examine the social, political, and economic impacts of industrialization on early 20th century society.

Materials:

- PBS: New York, Disc 4

- Triangle Shirtwaist Fire PowerPoint (RS#18)

- Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Document Analysis Sheet (RS#16)

- Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Document (RS#1-15)

- Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Assessment (RS#17)

Procedures:

Step 1: Initiate the History Lab

- Use the film clip from PBS "New York: Disc 4" starting at 79 minutes [Chapter 9] into the film as a motivation activity. Stop the disc at 95 minutes which is when the documentary shifts from describing the fire to the aftermath. As students view the film clip, have them jot down notes on the top portion of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Document Analysis Sheet (RS#16) and discuss the who/what/where/when/why aspects of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. This will help provide a context for students to understand the nature of the disaster. From this point, students will be ready to get into the lab. Note: If you are unable to acquire the PBS documentary, an alternate method to cover the fire background can be found at websites such as: http://www.historybuff.com/library/refshirtwaist.html and http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/Trianglefire/

- Explain the fact that unions had tried and were unsuccessful in trying to remedy the problems that led to the fire at the conclusion of the film clip. Using the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire PowerPoint (RS#18), project the Uprising of 20,000 song. Use this document as a model for document analysis. Ask:

- Who is the author of this document?

- What does the text of this document tell us?

- Is there any reason to doubt the accuracy of this account?

- Lead a class discussion based on the document. Students should note that a union wrote the song, there was a strike, it happened in the winter of 1909, and it was violent but they won. Explain the Uprising of 20,000 in 1909 began when Triangle Shirtwaist employees struck for better wages and safer conditions. The women were often met with violence and arrested. Though the union was "successful" in bargaining some changes such as increased pay and better working conditions, none of the agreements were followed through, ultimately leading to the fire.

Step 2: Frame the History Lab

- Introduce students to the overarching question, "Who should bear responsibility for the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire?" You may ask students to predict blame but do not spend too much time here.

Step 3: Facilitate the History Lab

- Present each student with a series of documents found on the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Documents (RS#1-15). Divide students into groups and assign each group two to three documents - depending on ability. Have students complete the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Document Analysis Sheet (RS#16). Students can also be encouraged to work independently for the first few minutes on the documents and then form pairs to share ideas with their partner in lieu of working in groups.

- Note: You can modify this lab by using fewer documents depending on student's ability. Be sure when selecting documents to choose documents giving the students multiple choices for how to assign responsibility for the fire. You would need to include documents that point the blame at the building owners, labor unions, government (inspectors, fire department, lawmakers, etc.), workers, and Harris and Blanck in order for student to be able to complete the assessment activity. A minimum of 6 documents is suggested.

Step 4: Present information and interpretations

- Facilitate an informal presentation/discussion so students can present their findings to the class and explain their documents. Initially, students should explain who the source believes was responsible for the deaths of the workers. Then, the students should explain how the authorship of the document affects the quality of information being presented. As each group presents, remind students to complete their organization chart (RS#16) for each source as they are presented. The teacher or students can also record the information on a chalkboard, whiteboard, overhead, or Elmo (document camera) for all students to view.

Step 5: Connect to the overarching question

- Teacher will ask the following questions to the entire class in order to connect the documents to the larger question.

- What is the general tone of the sources?

Answers could include angry, outraged, condemning, melancholy, etc.

- What are some of the common threads between the sources?

Answers could include that many of the sources were magazines and newspaper articles. Many of the sources condemning of the factory owners while few placed culpability in the hands of the workers themselves. Many sources also demand responsibility be taken by someone/something.

- What are some of the differences between the sources?

Answers may include that some of the sources are more strongly worded than others, they vary in degree of sensationalism, or they emphasize different group's responsibility.

Step 6: Assess

- Distribute the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Assessment (RS#17) and instruct students to complete the assessment. Be sure to emphasize to the students that they must use evidence found in the lesson when justifying their responses.

- If time remains, encourage students to share their responses to share their final assessment.

RS#01: This is One of a Hundred Murdered

Text: This cartoon was created by Thomas Dorgan and published in the New York Journal. The text of the document shows a deceased Triangle Factory employee lying on the sidewalk. It says "This is one of a hundred murdered. Is any one to be punished for this?" It also has a sign that says "Operators wanted on the 9th floor."

Context: This cartoon was drawn after the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. It was made at some point in 1911 but it is not clear if this was created before or after the acquittals of Blanck and Harris.

Subtext: indicates the author is frustrated with either the lack of culpability by the factory owners, building owners, or the government. It also could indicate the frustration of the acquittal of Blanck and Harris but the exact date of the document is not known.

Relation to Focus Question: It demands responsibility for the fire but does not make a clear indication of who or what is responsible. However, the document is likely vilifying Harris and Blanck.

Dorgan, Thomas Aloysius, "This is one of a hundred murdered." Cartoon, The New York Journal, 1911. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/photos/photo_enlargements.html?image_id=70&sec_id=10&image_type=cartoon (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#02: Testimony of Ethel Monick

Text: This document is a transcript of the testimony of Ethel Monick. The testimony was given in court during December, 1911. She describes her experience when the fire broke out in the factory.

Context: This testimony was given during factory owner Harris and Blanck's trial for manslaughter. The prosecution had to prove that Harris and Blanck intentionally locked the women in the sweatshop.

Subtext: Ethel explained that the door was locked when the employees were trying to escape. In doing this, she is trying to pin blame on the owners Harris and Blanck for the death of her coworkers. In claiming that she was scared of the owners, she was undoubtedly trying to sway the jury to find them guilty. However, the defense tries to discredit her testimony.

Relation to Focus Question: This document indicates that it was the fault of Harris and Blanck for the deaths of the Shirtwaist employees. It makes no mention of other factors.

Excerpts from Trial Testimony in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial." Famous Trials: The Triangle Shirtwaist Trial 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/triangletest1.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#03: Say Triangle Doors Were Never Locked

Text: This is an article written for the New York Times on December 21st, 1911. The title of the article is "Say Triangle Doors Were Never Locked: More Witnesses Contradict the Testimony of Harris & Blanck's Girl Employees." The defense presented shirtwaist employees in the trial who testified t hat Harris and Blanck did not lock the doors without having an available key in it at all times.

Context: This article was written one week before the acquittal of Harris and Blanck. Since the prosecution had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they had intentionally locked the girls in the sweatshop, this testimony could have been key in ensuring their acquittals.

Subtext: The New York Times was known as a more objective news source in the era of yellow journalism. Their competitors such as The New York World and the New York Journal were known for producing more sensational reports and were publishing biased accounts against Harris and Blanck.

Relation to Focus Question: This presents interesting contradictory evidence that Harris and Blanck may not be as culpable as students would like to believe. The fact that two employees both testified that they did not lock the doors greatly muddled the waters for Harris and Blanck.

The New York Times. "Say Triangle Doors Were Never Locked: More Witnesses Contradict the Testimony of Harris & Blanck's Girl Employees" December 21, 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglenyt1221.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#04: Holding the Door Closed

Text: This cartoon was created by an unknown author and published in the New York Journal on March 31, 1911. The text of the document shows girls trapped inside the factory while an unnamed money interest holds the door closed.

Context: This political cartoon was published about a week after the fire occurred. There still had not been the public funeral procession and Harris and Blanck had not been indicted. However, public debate had already begun over what kinds of new regulations should be enacted to provide safer working conditions.

Subtext: This publication was owned by William Randolph Hearst, one of the founders of sensationalized reporting known as yellow journalism. It was a direct competitor magazine with the likes of New York Times and New York World.

Relation to Focus Question: This cartoon is interesting in that the culprit trapping the girls inside the building is unknown. One can only determine that it is some sort of money interest - perhaps the factory owners or perhaps the building owners. Students should justify who they think is being incriminated in this cartoon but emphasize that there is no conclusive answer.

"Holding the Door Closed." Cartoon, The New York Journal, March 31, 1911. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/photos/photo_enlargements.html?image_64&sec_id=10 (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#05: Frances Perkins Lecture

Text: This speech details an eyewitness account of the triangle fire. It was given by Franscis Perkins 53 years after the fire. Perkins happened to be in New York on the day of the fire and watched the horrific events unfold in front of her. She gives a chilling account of the fire itself and who she thinks is to blame.

Context: This speech was given at Cornell University 53 years after the fire was occured. Of all the documents this has the most hindsight. Students should note what may happen to a person's account after so much time has passed.

Subtext: Francis Perkins life was changed from witnessing the Triangle fire. Because of this fire, she became a dedicated labor activist and emerged a well-known progressive. She was later appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt as the Secretary of Labor - first woman to ever be appointed to the presidential cabinet.

Relation to Focus Question: The new information presented in this document is not the incrimination of Harris and Blanck, but rather their motives in allegedly chaining the doors shut. She claimed they chained the doors to prevent women from stealing shirtwaists. Students should be reminded that this conclusion is still speculative.

Perkins, Francis. The Triangle Factory Fire. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire (accessed June 29, 2010).

RS#06: Blame Shifted On All Sides for Fire Horror

Text: This article appeared in the New York Times three days after the fire. In reading this document one gets a sense of the "blame game" beginning in the public. Among the culprits directly named are t he inept local government officials and also Harris and Blanck.

Context: Since this article was published so soon after the fire, there was only speculative blame to be assigned. The bodies of t he victims had only been identified two days earlier and there still hadn't been the massive funeral procession.

Subtext: The Times was known for being less sensational in their reporting then their competitors such as New York World.

Relation to Focus Question: This document asserts the government is the most culpable party and alludes to the fact that Harris and Blanck may be as well. They single out the Building Department for failing to enforce adequate fire escapes and doors that open outward. Interestingly, the government fired back by insisting that t he Asch Building had met all codes required by law. The end of the article adds that Harris and Blanck may have locked the door, according to fire chief Croker.

The New York Times. "Blame Shifted On All Sides For Fire Horror" March 28, 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglenyt4.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#07: Inspector of Buildings!

Text: The title of this cartoon is "Inspector of Buildings!" It depicts an inspector dressed as an agent of death. His hand touches a sign saying "Record fire for New York 145 LIVES LOST!!! Building Fire Proof. Only fire escape collapses. [unknown] Fire Inspector."

Context: The date of this publication is unknown but it could be perhaps from a week or two after the fire when the public frenzy was directed more towards the government since the Harris and Blanck trial had not yet begun.

Subtext: Though the source is unknown, it is likely this cartoon came from the New York Journal, a publication known for its sensational reporting. The cartoon style is characteristic of the other New York Journal cartoons.

Relation to Focus Question: This cartoon places responsibility squarely on the shoulders of the government. The cartoon insists that the Building Department allowed the dangerous working conditions to exist, even within the law, and were therefore to blame. Again, the building owners were likely complying with law so it is therefore the lack of government oversight that allowed this tragedy to occur.

"Inspector of Buildings!" Cartoon, http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/photos/photo_enlargements.html? 7&sec_id=10&image_type=cartoon (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#08: Triangle Owners Acquitted by Jury

Text: This newspaper article details the day the jury acquitted factory owners Harris and Blanck of manslaughter charges in the first and second degree. After the jury voted to acquit them, the defendants were escorted out of the courtroom in fear of their safety. Interestingly, the end of the article lists the name and address of all the jurors in the trial.

Context: This verdict came after an emotionally charged trial that lasted from April until the end of December. It was the burden of the prosecution to prove that Harris and Blanck had willfully and deliberately locked the Triangle employees in the factory. After much contradictory evidence, it seems that the jurors could not prove their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Subtext: The Times newspaper was known for being less sensational ini their reporting than their competitors such as New York World. However, one must note that t he author/editors of the paper may not have been pleased with the outcome of the trial if they published the name and addresses of the jurors who acquitted the factory owners.

Relation to Focus Question: Though the article details the final day of the Harris and Blanck trial, it may slightly lean towards being unsatisfied with the verdict. It tries to give balance to the story and respect for the justice system but ultimately there is a sense of injustice. There are emotionally charged statements, the description of the covert exit of the defendants and the listing of juror information adds up to dissatisfaction.

The New York Times. "Triangle Owners Acquitted by Jury." December 28, 1911. http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/triangle/trianglenyt1228.html (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#09: 147 Dead, Nobody Guilty

Text: There is serious tone of indignation in this editorial. The author gives a scathing criticism of the fact that 10 months after the tragedy; no one seems to be culpable, not Harris and Blanck, not the factory owners, not the government, not anyone.

Context: The publication of this opinion editorial came a little over a week after the acquittals of Harris and Blanck but 10 months after the fire itself.

Subtext: This magazine publication included many opinion articles and an analysis of news events. The following source is an opinion article written by an unknown author.

Relation to Focus Question: The tone of this article may be indicative of the general public mood regarding the fire. Considering the fire had occurred 10 months prior, there is still an emotionally charged atmosphere surrounding the event. It seems that the public had not yet forgotten the incident and it was not going to blow over quietly.

Literary Digest. "147 Dead, Nobody Guildy." April 29, 1911. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/ texts/newspaper/ld_010612.html?location=Investigation,+Trial,+and+Reform (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#10: The Locked Door!

Text: The title and only caption in this cartoon is "THE LOCKED DOOR!" It is dramatic depictions of women jammed against the door trying for their lives to get out of the fire but are slowly being swallowed by flames.

Context: Through the publication date is not known it is possible this happened either just before or during the trial of Harris and Blanck.

Subtext: Though the source is unknown, it is likely this cartoon came from the New York Journal, a publication known for its sensational reporting. The cartoon style is characteristic of the other New York Journal cartoons.

Relation to Focus Question: Though not explicit, the cartoon is indicting towards Harris and Blanck. This conclusion is based on the fact that "THE LOCKED DOORS!" is the only text and that the factory owners were alleged to have deliberately locked in their employees.

Unknown author. "The Locked Door!" http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/photos/photo_enlargements.html?image_id=68&sec_id=10&image_type=cartoon (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#11: Placing the Responsibility

Text: This magazine article explains why Harris and Blanck were charged with manslaughter of two of their female employees. It goes into detail of how the doors may have been locked and also how the working conditions were wretched. The article concludes by recommending increased government regulations.

Context: This article follows two weeks after factory owners Harris and Blanck were charged with manslaughter for locking the factory doors.

Subtext: Similar to the Literary Digest, this publication was a weekly news and opinion magazine aimed especially at New York City residents.

Relation to Focus Question: Though no verdict had been determined, there is detectable contempt for Harris and Blanck. There were also very specific recommendations for better fire regulations at the end of the article, pointing out that the author believes government negligence was also at hand.

The Outlook. "Placing the Responsibility." April 29, 1911. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/newspaper/outlook_042911.html?location=Investigation,+Trial,+and+Reform (accessed June 28, 2010).

RS#12: Chairman's Report, Fire Prevention Committee

Text: This report by Dr. George Martin Price, chairman of the Fire Prevention committee, paints a bleak picture of the safety conditions of over 1,200 factories in New York City. He gives statistical analysis of his factory inspections and the results are terrifying. He then goes on to charge that the current regulations are completely insufficient because significant fire hazards exist even within the parameters of the law - going as far calling current regulations a "delusion and a sham."

Context: This report was released a mere two days after the Triangle fire. His findings demonstrate that a significant number of factories could face deadly consequences if a fire breaks out.

Subtext: Though not explicitly saying it, the Fire Chief fears that the fire dangers across the city are were not unique to the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. There is a dreadful tone to his report that hundreds if not thousands of other factories could face the same fate.

Relation to Focus Question: The culpability in this document rests squarely on the government. The chairmen not only uses statistics to prove that the factories across New York City are grossly out of compliance of existing regulations, but he goes further in pointing out that existing regulations are completely ineffective and offer no real protection. He believes it is the government's responsibility to dramatically increase regulatory standards and enforcement of those standards.

McClellan, Jim R. Changing Interpretations of America's Past. 2nd ed. Vol 2. McGraw Hill, 2000.

RS#13: Murdered by Incompetent Government

Text: This newspaper article in the New York World provides an editorial account of Fire Chief Croker's findings and echoes his sentiments. The chief describes the lack of fire escapes, the fact that the building was not "fire proof" as it was alleged to be, the inadequacy of elevators for emergencies, and recommendations for a safer building.

Context: This story came two days after the burning of the Triangle factory and also provides evidence that there had recently been a tragic industrial fire in Newark, New Jersey.

Subtext: This New York City based newspaper was known for its sensational reporting style (yellow journalism) and was a direct competitor with The New York Journal and The New York Times. Fire Chief Edward Croker, though related to Boss Croker, was an outspoken critic of building codes and an advocate for increased fire fighting technology. Feeling disheartened by the prospect of real and tangible change after the fire, he resigned as Fire Chief.

Relation to Focus Question: This article places culpability on the government as well as the building owners. According to this article, the government had obviously failed to protect the workers with sound and sensible regulations. On the other hand, the building owners provided minimal safety protection by installing cheap and flimsy fire escapes which melted instantly in the blaze.

McClellan, Jim R. Changing Interpretations of America's Past. 2nd ed. Vol 2. McGraw Hill, 2000.

RS#14: Testimony from the Factory Investigation Commission

Text: Abram Elkus insists that working conditions can kill a human as easy as a gun or club. He urges government intervention to prevent such tragedies and he blames greed on all accounts.

Context: This statement was given 6 months after the triangle fire. Harris and Blanck were still on trial with no verdict yet.

Subtext: In the aftermath of the fire, Abram Elkus was actively involved in creating legislation dealing with child labor, working hours for women, fire protection, and similar safeguards for factory workers.

Relation to Focus Question: In true tone of the Progressives, Elkus believes that the government has a responsibility to improve working conditions. He also believes that it is greed that caused this tragedy, thereby indicting factory owners Harris and Blanck as well as the building owners for failing to provide minimal fire protection.

McClellan, Jim R. Changing Interpretations of America's Past. 2nd ed. Vol 2. McGraw Hill, 2000.

RS#15: Rose Schneiderman Speech

Text: The author is calling for increased union solidarity and activism in order to achieve safer working conditions for sweatshop workers. She indicates that other fires have occurred and women workers are in constant danger in their workplace.

Context: This speech was given shortly after the fire for mostly shirtwaist trade workers. She is using the recent tragedy in order to push for increased unionization.

Subtext: The author is an outspoken advocate of socialism. She was also a prominent union organizer whose activities also included the Uprising of 20,000.

Relation to Focus Question: Rose Schneiderman's speech is a quality example of the fact that unions, especially within the sweatshop industry, were unable to secure real change and safety measures for their workers. This will help students weigh the fact that women's unions, including the ILGWU, had unsuccessfully pushed for safety measures in the workplace.

Leon Stein, ed., Out of the Sweatshop: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy (New York: Quadrangle/New Tiimes Book Company, 1977), pp. 196-197.