Author:Lawrence Miller, Baltimore City College, Baltimore City Public School System

Grade Level:High

Duration:1-2 periods

Overview:

Optimism and a "can-do" attitude are qualities associated with the so-called American character. In some circumstances, however, over-zealous enthusiasm could lead to economic and environmental catastrophe. Such was the case with the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Poor commercial coordination, over-farming, and, policy mistakes in Washington led to one of the worst episodes of the Great Depression -- not in the offices of Wall Street, but in the fields of the Southern plains, where unstoppable dust storms ruined the lives of thousands of families.

This lesson explores the causes, responses to, and consequences of the Dust Bowl in early twentieth century America.

Content Standards:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Standard 1: The causes of the Great Depression

affected American society

Historical Thinking Standards:

Standard 1: Chronological Thinking

A. Distinguish between past, present, and future time.

Standard 4: Historical Research Capabilities

C. Interrogate historical data.

D. Identify the gaps in the available records, marshal contextual

knowledge and perspectives of the time and place, and

construct a sound historical interpretation.

Lesson Objectives:

• Students will analyze primary source photographs to identify historical perspectives.

• Students will compose a narrative to illustrate the American experience for those who

lived in the Dust Bowl.

What are the predominant images we have of the Dust Bowl? Clouds of dust blocking the noonday sun. Barren fields stretching to the horizon. Dust-choked small towns. Family groups - males in tattered overalls, females in plain dresses. Finally, one may recall long lines over-burdened cars and trucks heading west to "golden" California.

These images suggest that people faced an overwhelming natural disaster, and they reacted to it with dignity and stoicism. There is merit to this conclusion, but there is more to the story.

The region - parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas - opened to white settlement in the mid and late nineteenth century. After a few years, commercial farming of food grains was the primary activity. Commercial farming meant that grain and other products had to be brought to market, and this meant that farmers had to deal with the railroads. Also, despite the operation of the Homestead Act that attempted to provide land at nominal cost to settlers, farmers also incurred debt for land and for farm machinery that was becoming available because of the industrial revolution then transforming the nation. "Debt" brings the banks into the picture. As farm productivity increased, as international transportation improved, as more foreign lands were brought under the plow, commodity prices fell as supplies exceeded demand. Agricultural products flooded markets, and farmers, distributors, processors, and others had to slash prices to sell their products. Farm expenditures remained artificially high because of railroad policies and protective tariffs. To try to make up for falling prices and relatively high expenses, farmers tried to bring more and more land under cultivation, even some land that was marginal or needed a high level of skill to be farmed effectively.

Farming on the plains was different from farming the Ohio Valley or east of the Appalachians. The east was originally heavily forested and had abundant rainfall that fell in approximately the same amounts year after year. Topsoil was rich, and the formers could grow a variety of crops depending on their soil and market conditions. The east was more densely populated providing more of a local market for agricultural goods or employment during slack periods.

Farmers on the plains did not have these advantages. As one moves west into the region, the amount of forested land decreases until one finally encounters grasslands. The sod is thick and needs to be plowed repeatedly so that plants could take root and grow. This became easier later in the period as farmers used tractors to pull discs and harrows. Average annual precipitation was much lower in this region, and, as one approaches 100? longitude, could decline to insignificant amounts in an erratic pattern. Only certain plants could thrive under these conditions. This region also had a lower population density.

There was also something of a "bonanza" mentality as well. Lured by vistas of virgin land, lured by advertisements by railroads promoting the riches one could earn in the west, lured by an opportunity to start anew away from the settled east, people moved west dreaming of profits at low risk. And, if things didn't turn out as one hoped, one could move further west and try again. Farmers may have felt a spiritual attachment to the land and may have felt that they were the repository of all that was good in American culture, but they were also operators of businesses where the bottom line of profit or loss was calculated to the last penny. Whether through ignorance of the appropriate farming techniques or the desire to wring a profit from the land, farmers attacked this fragile environment with gusto. There were good years, and there were certainly many people who attained their dreams, but hard environmental reality and hard economic constraints meant that there were also many who found that farming was tenuous occupation and that their dreams would not be realized.

It should come as no surprise that this was also the region where the Populists found a receptive audience. The Populists emerged in the 19th century out of the older Farmer's Alliance. The Populists tried to protect the farmers from the vicissitudes of life that had become more complex, more difficult, more threatening. Preaching the iniquity

of railroads, processors, Wall Street, and the contagion of immigrant-filled cities, the

Populist thundered against threats to their way of life. William Jennings Bryan captured the Populist spirit in 1896 when he pronounced in his Cross of Gold speech, "Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country."

This spirit persisted into the new century when fellow Nebraskan George W. Norris said in 1911,

It is in the city&that there exists the most danger to perpetuity of our institutions. ..it is also in the city that we have the slum and breeding places of anarchy, ignorance and crime. It is there we have the mob. &

On the other hand, upon the farms are located the conservative, patriotic, and thinking voters of the country. &[T]hey are the balance wheel of our form of government. In time of danger and in time of war we lean with confidence upon the strong arm and the willing and patriotic heart of the

American farmer.

Farmers of this region had been on an economic rollercoaster since before the First World War. There had been a sharp depression in the 1890s and a smaller downturn when Theodore Roosevelt was President. Commodity prices rose, however,

during World War I. While one can mark the beginning of the Great Depression with the Wall Street Crash in 1929, many other segments of the economy were in decline well before this point. This was certainly true for the farmers of the region under study whose depression began in the early or mid-1920s. It might seem amazing to our

contemporary eyes, but even Oklahoma's new oil industry faced hard times because of transportation, refining, and government policies.

Nothing seemed to help. There certainly wasn't much help from the federal government. Secretary of the Treasury Mellon pursued a regressive tax policy. Tariffs were high culminating in the disastrous Smoot-Hawley tariff that raised rates to the highest level in American history to that point. Specific programs to help farmers such as the McNary-Haugen bill were never enacted. This bill, vetoed several times, would have required the federal government to purchase surplus commodities and sell them overseas, if necessary, to support domestic prices.

Farmers of the region also felt threatened by cultural patterns. Farmers echoed the earlier sentiments of William Jennings Bryan and George W. Norris when they

asked, "What is happening to our country?" Their core values - hearth and home,

status in the community, church, sobriety - seemed to be threatened by forces beyond their control. The new technologies, for example, seemed to be both a blessing and a curse. Movies brought the antics of Charlie Chaplin, but they also brought the exotic appeal of Rudolf Valentino and the eroticism of Clara Bow. The radio brought the world to the living room, but it also brought hucksters and jazz. The automobile was a tremendous convenience, but it also relaxed the reins of parental control over teenage

children. How does one respond? One can try to restore traditional values via the evangelism of Aimee Semple McPherson and Billy Sunday. One can expunge the

threat to the minds of children by keeping �false' ideas like Darwinian evolution out of schools as the state of Tennessee attempted to do. One can try to limit the threat of

alien influences through immigration restriction, Prohibition, and the Ku Klux Klan.

And then it stopped raining. And the winds began to blow. The fragile land eroded as winds lifted millions of tons of topsoil into the air and created smothering dust storms. Farming became nearly impossible. Small proprietors defaulted on loans and lost their land. Tenants and sharecroppers were forced off the land. Businesses and towns who depended upon the farmers failed as well. As people exhausted their savings, they faced difficult choices: Tough it out, depend on the charity of relatives,

move to the city, or move out of the region. Some of the more adventurous - or more

desperate - among them decided to take their chances in California.

Bibliography:

Burns, James McGregor. Roosevelt: Soldier of Freedom. New York: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, 1970.

Burns, James McGregor. Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox. New York: Harcourt, Brace,

1956.

Egan, Timothy. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of those who Survived the

Great American Dustbowl Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

Davidson, James West and Mark Hamilton Lytle. After The Fact: The Art of Historical Detection. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1992.

Gregory, James. American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in

Califortnia. New York: Oxford, 1989.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. Crisis of the Old Order, 1919-1933: The Age of Roosevelt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1957.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. New York: Oxford, 1979.

Depression: A long-term economic state characterized by unemployment and low prices and low levels of trade and investment.

Dust Bowl: An area of the US Plains that included parts of Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. The term was coined in the 1930s, when dry weather and high winds caused many dust storms throughout the United States, but particularly in this area.

Drought: An extended period where water availability falls below the statistical requirements for a region.

Erosion:The wearing away of land or soil by the action of wind, water, or ice.

Migrant: A person who leaves their region of origin to seek residence in another country.

Sharecropper: One who gives a share of his crop to the landowner in lieu of rent.

Tenant Farmer: One who resides on and farms land owned by a landlord. The rights the tenant has over the land, and the form of payment, varies across different systems.

1. As a motivational activity ask student the following questions:

What makes a good story?

What is a plot? Character? Setting?

How do these elements make a story interesting?

Discuss that the basis of history is a story. It can be the story of famous people

like Abraham Lincoln or Martin Luther King. It can be the story major events like

the Civil War or the struggle for civil rights. But history can also be the story of

people who aren’t famous or events that have only a paragraph or two in the

history books or might not even be recorded at all.

Explain that the story that the class is going to try to tell is the story of the Dust

Bowl and what happened to the people who lived there in the 1920s and 1930s.

2. Ask:

What is needed to tell this story?

Student responses may include, but not be limited to:

a) Maps

b) Film

c) Stories

d) Secondary Sources

e) Primary Sources

f) Narratives

g) Newspapers

h) Government reports

i) Photos

3. Create groups of about three or four students each. Provide each group complete copies of the following Resource Sheets:

Resource Sheet #1, “Dust Bowl Refugee in California”

Resource Sheet #2, “Depression and drought struck towns”

Resource Sheet #3, “Children of Oklahoma drought refugees”

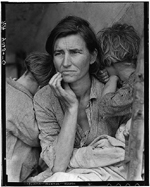

Resource Sheet #4, “Oklahoma mother of 5 children”

Resource Sheet #5, “Mailbox in Dustbowl”

Resource Sheet #6, “Abandoned Farm in Oklahoma”

Resource Sheet #7, “California 1936”

Resource Sheet #8, “Dust Storm in Oklahoma”

Resource Sheet #9, “Famers”

Resource Sheet #10, “Father and Sons Walking in the Face of a Dust Storm”

Resource Sheet #11, “Document Analysis Form”

4. Tell students that they will try to rely exclusively on photos to tell our story.

Have them select one or two pictures to discuss as a group and complete

Resource Sheet #11 for each.

5. After students have completed the activity ask:

Can we tell a story with the pictures?

6. Have the students attempt to place the photos in some sort of sequence. They

should use as many of the pictures as possible. Students can exclude some of the

photographs, but should be able to tell reasons why they were disqualified. Ask:

Do we have enough pictures? What might be missing?

7. Have students write a story that includes plot, character, and setting. Students

may write stories either directly from the pictures or inspired by the pictures.

8. As a closing activity ask:

What advantages and disadvantages did we discover while trying to use

pictures to tell a story?

What did we learn today about the lives of ordinary Americans who lived

through the Dust Bowl experience?

9. In order to assess understanding, evaluate students’ stories to determine the

extent to which they used the photographs to create a narrative.

10. A possible extension activities is to provide students with a copy of Resource

Sheet #12, “Migrant Mother,” and have individuals or groups of students construct

a paragraph answering the question:

What is she thinking?

All of the photos come from the American Memory collection in the Library of Congress

(http://memory.loc.gov). There are a multitude of photos at this site, and one could have very

easily selected a number of other different sets of documents to present to the students. The

pictures try to represent a number of themes/ideas: (1) the land and the devastation of the dust

storms (2) farm life (3) scenes from towns (4) the migrants’ experience in California.

Almost all of the photos come from the FSA project and many of them are by Dorothea Lange.

It is not my explicit intention to develop the motivation of the agency or the photographers, but

these are significant ideas that could be developed in subsequent lessons.

The following are the catalogue numbers (Digital ID) for each of the photographs:

ppmsc 00241 Farmer and sons walking in the face of a dust storm

fsa 8b38298 Dust storm Oklahoma

fsa 8b13000 California 1936

fsa 8b32000 Abandoned farm in Texas

fsa 8b32342 Mailbox in Dustbowl

fsa 8b29516 Migrant mother

fsa 8b32402 Depression and drought struck towns…

fsa 8b29828 Oklahoma mother of 5 children…

fsa 8b31646 Children of Oklahoma drought refugees…

fsa 8b27016 Dust Bowl refugee in California…

fsa 8b29736 Farmers

fsa 8b38293 Abandoned farm in Oklahoma

fsa 8b31958 West Texas family farm